One does not turn to James Wright for laughter, so it came as something of a surprise to find him writing a tribute to the Italian satirist Giuseppe Gioachino Belli. The tribute appears in Wright’s last collection, the posthumous This Journey (1982), and was fashioned in Belli’s own favored form, the sonnet, making it the second to last of Wright’s half-dozen and the first after many years, indeed the first after “Saint Judas” (1959), the celebrated title poem of Wright’s last book in which traditional form was the rule.[1]

Half a dozen is not a large number, but Wright made his mark in the sonnet before abandoning the form: his “Saint Judas” is one of 92 poems from the previous century chosen by Daniel Bromwich for American Sonnets (2005), a slender anthology from the Library of America.[2] Inspired by Belli or not, Wright’s return to the sonnet in This Journey, a book composed at the end of his life — he was dying of cancer at the time — must have functioned for the longtime reader of his work as a kind of rhyme, both well-prepared for and unexpected, yielding to a need, or at least desire, for formal closure, while offering up the pleasure of surprise.

The rhyme, it should be said, is not a couplet, but an envelope, coming after two decades of free verse, drawing a link between one kind of last book and another. The subject too creates a kind of envelope rhyme, drawing a link between two temporally disjunct figures: Wright wrote his doctoral thesis on Charles Dickens (and so, presumably, had an appreciation for humor, if not the gift or inclination to produce it), while Belli, a contemporary of the novelist, had Dickens’s ear for dialect and a comparable sympathy for the poor. Call it an off-rhyme, as Belli’s sympathy was not displayed with tenderness but outrage. His humor was decidedly populist: Belli brought a low comedy to bear on high subjects, most notably the popes (drawing the admiration of James Joyce), and expressed himself in the vulgar tongue of his native Trastevere — the language of Rome, Romanesco. Wright had his own love of the vulgar but his method was very nearly the opposite: he brought a high sense of tragedy to bear on the low — it was the darkness in Dickens to which he was drawn; and he expressed himself, even in free verse, in “a conspicuously mannered style” (quoting here from a review of This Journey) “derived neither from speech nor from traditionally fluent writing.”[3]

Piazza Giuseppe Giacchino Belli in Rome (photo by Dr Martinus)

Given all this, it is not surprising that Wright should discover a tragic comedy in Belli. The one poet disdained, the other pursued, a project of dignification, but the two shared a deep appreciation of indignity’s power, though that power was mobilized in very different ways. Wright reflected on it, Belli conferred it. Wright’s tribute to Belli closes the circle, reflecting on the indignity conferred on Belli himself. This topic of reflection might, in other hands, at other times, produce something other than a tribute, but Wright had good reason to identify with Belli beyond the bare fact that both were poets. As his title indicates, Wright’s sonnet concerns the poet’s embrace by posterity, and Wright was aware, of course, in composing it that this embrace would soon be his own. Contemplating Rome’s monument to Belli, Wright saw that such tributes are a mixed blessing, and so decided to add his own prayer to the mix — his own inscription, as it were, on the monument to poetry that the sonnet itself represents:

Reading a 1979 Inscription

on Belli’s Monument

It is not only the Romans who are gone.

Belli, unhappy a century ago,

Won from the world his fashionable stone.

Where it stands now, he doesn’t even know.

Across the Tiber, near Trastevere,

His top hat teetered on his head with care,

Brushed like a gentleman, he cannot see

The latest Romans who succeed him there.

One of them bravely climbed his pedestal

And sprayed a scarlet ᴍᴇʀᴅᴀ on his shawl.

This afternoon, I pray his hidden grave

Lies nameless somewhere in the hills, while rain

Fusses and frets to rinse away the stain.

Rain might erase when marble cannot save.[4]

Not quite a prayer for oblivion, the poem extols the hidden and nameless, preferring the valet-like service of the rain (which fusses and frets over the dirtied gentleman) to the magisterial efforts of the stone. The stain here is not sin, but insult, yet that final word “save” does suggest a contrast between the humility of Christ and the majesty of the Church, a contrast with no small significance in Belli’s own poetry. The ironies are clear, so clear one might not take care to notice that this Christ-like rain is not tendering its care to Belli, who lies elsewhere, but to the Church — if I might put it that way — erected in his name. A river divides Belli from his posterity, and Wright, standing on this side, has already passed over in his care to the other.

◊

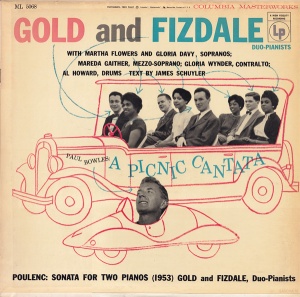

Ray Johnson cover for The Roman Sonnets of Giuseppi Gioachino Belli (Jargon Press, 1960) (image by way of With Hidden Noise)

Wright is not a poet with any presence in the NPF’s publications, and I find only one session in which his work was discussed at any of our conferences, but a few months ago, visiting Jamestown Community College, I found myself in a lunchtime conversation with the brother-in-law of Wright’s widow, and since then I’ve done some modest dipping in and out of Wright’s work. (The brother-in-law, I should say, was the president of the college, which made this the most interesting conversation I’ve ever had with an administrator.) Wright, in turn, led me to Belli, whose link to the NPF is, paradoxically, much stronger: Harold Norse’s lively translations were published by Jonathan Williams with an introduction by William Carlos Williams. That introduction is primarily concerned with language: Belli’s Roman dialect and the American idiom with which Norse created his translations. Williams is charmed by the use of such language by “the sonnet, of all forms, so used to being employed for delicate nuances of sound and sense.” I suspect he would not have had much use for Wright’s poem, though his summary of Belli’s accomplishment captures well the complex relation of high and low that Wright shares with Belli, and that Wright captured in his own way in his tribute:

The times were crude, especially so for the underdogs with whom these sonnets deal, but not so crude that they could not see themselves, in their imaginations, in high office. Belli saw it also and he knew how, politely, to bring them down — and up ! — to their betters by a knowledge of the language.[5]

A fair summary of Wright’s accomplishment too.

◊

Notes

1 [Back to text] I take the figure six from Above the River: The Complete Poems, ed. Anne Wright (1990). Three appear in Wright’s first book, The Green Wall (1957): “To a Troubled Friend,” “To a Fugitive,” and “My Grandmother’s Ghost.” After these comes “Saint Judas,” and then, after long pause, two last sonnets appear in This Journey: Wright’s tribute to Belli and “May Morning,” the latter an experiment in which a rhymed and metered sonnet is run together as prose (as noted by Kevin Stein in James Wright: The Poetry of a Grown Man, 138-39 and 198 n. 21, crediting Michael Hefernan with the discovery). Conceivably, Wright also thought of “Listening to the Mourners” as a sonnet. Its fourteen irregular, unrhymed lines appear in Shall We Gather at the River (1968).

2 [Back to text] I mean the century leading up the anthology itself.

3 [Back to text] The reviewer is Alan Williamson, writing for The New Republic. See James Wright: The Heart of the Light, ed. Peter Stitt and Frank Graziano, 411.

4 [Back to text] Wright, Above the River, 325.

5 [Back to text] William Carlos Williams, “Preface,” The Roman Sonnets of Giuseppi Gioachino Belli, n.p.