Kenneth Irby (with Kyle Waugh behind)

Soon after Kenneth Irby died I wrote something short that’s never seen light, which I thought to publish today—yesterday was the eighth anniversary of his passing. Information about his life and work is not plentiful online, but much can be gleaned from this Jacket2 symposium. And there are many recordings of Irby’s readings at PennSound.

A Friend Passes from the World

When intention remains but the I who intends steps away, letting the work unfold according to its own needs, though drawing on all the resources of self (craft, knowledge, memory), the work acquires a peculiar authority: modest yet resolute, shaped by an absence that lingers, ungrasped.

Kenneth Irby’s poetry continually summons him to mind, but he is gone.

The title of Irby’s collected poems, The Intent On, already tells the tale: an elided “i” breaks language open, moves on, leaves trail markers along the way. Those markers are the poetry. The trail—where does it lead?

Kyle Waugh, the book’s editor, has a lovely reading of this title:

The phantom “I” that cleaves intention into intent on also serves as the object of the title’s truncated predicate: intent on…what? Intent on seeking out a self “lost on off / in those steep and wandering canyons,” a self momently retrieved in and through the lifelong practice of daily writing.

This figure of the phantom I suggests to me a poet breaking through intention like a runner at the finish line—except that the tape hangs in air, a piece missing, while the runner keeps going, chasing a shadow. As a deformation of language, Irby’s “intent on” is a figure for the runner’s pierced line hanging in air. Finish line that does not finish.

Torn open, language cannot close.

Yet I am not sure I agree with Waugh’s conclusion, that the I who writes is what the writing seeks.

I hold to a belief that Irby’s writing unfolds according to other needs than his own.

His self is not the object of the search, but one of the dimensions in which searching occurs—an idea I find in the very poem Waugh quotes, “Relation.”

On first reading, Waugh’s quote tripped me up, owing to its awkward trinity of prepositions: “on off / in.” Going to the poem for clarification, I saw that the “canyon” of the quote is but one place of seeking in the poem; that there are two worlds in Irby’s text—the shared one outside, traversed by two historical figures (Cabeza de Vaca and Escalante, famed explorers of the American West); and the private one within, also traversed by them. The grammatically bewildering “on off / in” marks a moment of unexpected conjunction, in which the two worlds come together in experience, with the “self” lost “on” the surface of one world (“the plains in the mind / eroded to the Ground”) while yet wandering purposefully “off in” another (“those steep and wandering canyons” of the Southwest).

The pileup of prepositions, clear in context, performs a crucial mimesis, a representation in language of what the passage is all about—the coming together of inner and outer in the experience of exploration.

This coming together of inner and outer was no goal of the explorers themselves, indeed may have kept them from reaching their goal (as Irby suggests with regard to Escalante, who “only came back / where he had begun,… / …without touching California / or that western sea”). But coming together is certainly a goal of Irby’s. What he seeks is relation, a terminus only reached (or better, glimpsed) when one world confronts its end in the other.

As Irby describes it, this terminus sounds very much like the hole a runner makes in the tape at a finish line—here made by an explorer whose endless trek across the plains of the mind wears down the path until it opens underfoot, merging with that other path, mind and rock becoming one in the madness of the search.

Lost on a plain eroded in the wandering, one step at a time, the self disappears into the very distance it opens. The poem relates this disappearance.

We who receive this relation are, by definition, the ones who remain when the I takes off. In this sense, the title gives us title, bequeathing the work to those it creates: “the intent on” assembled when the I breaks through.

Intention is a provisional limit; we long to see it superseded, though it leave us with a hole.

A friend passes from the world.

His work remains; we become its finish line, torn by his departure

.

*

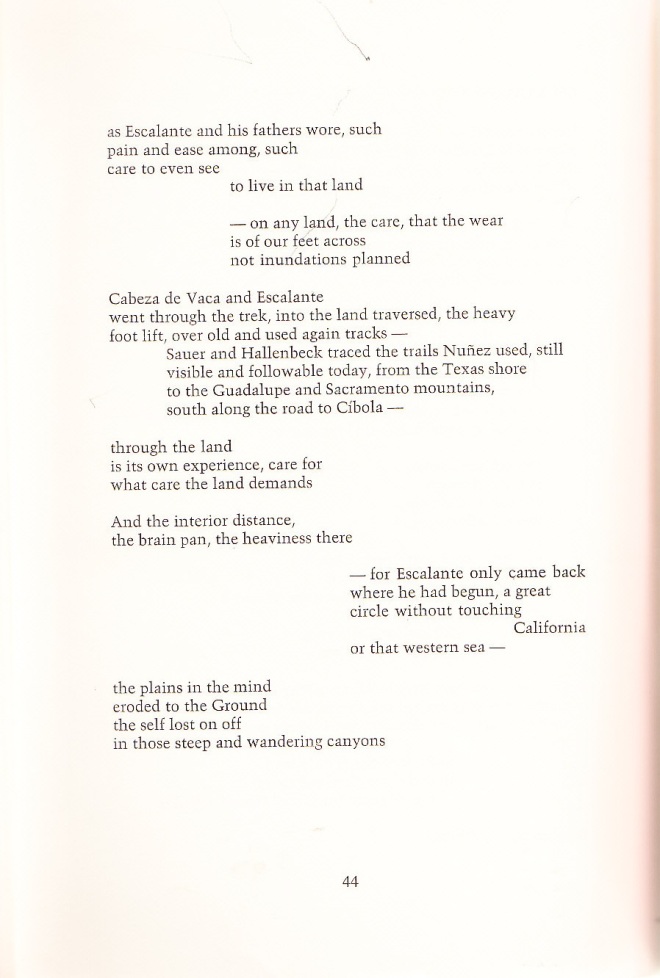

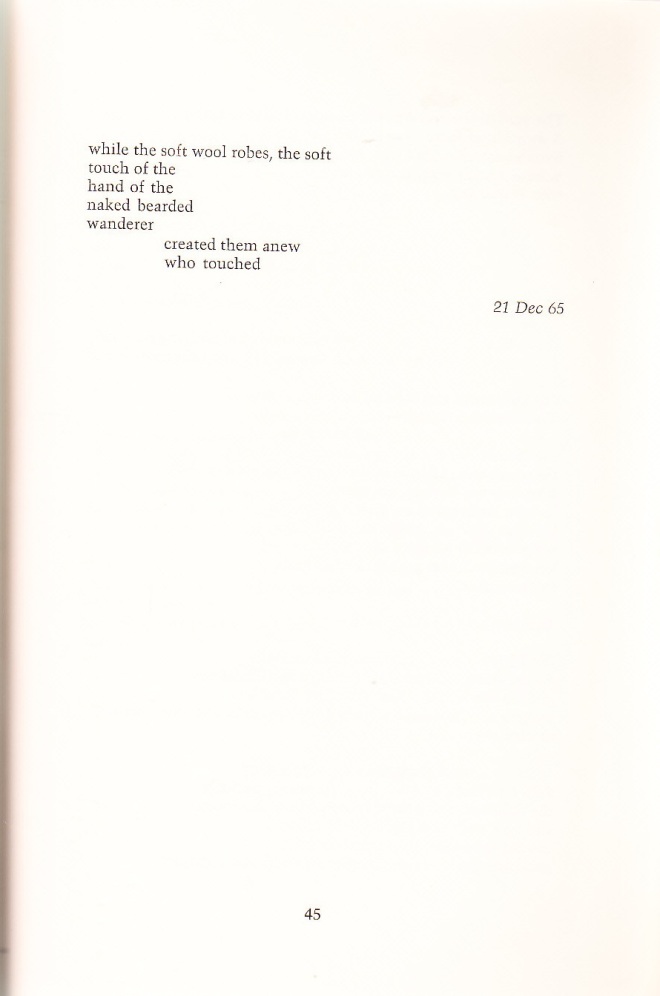

“Relation” is an early poem of Irby’s (written in 1965), and not representative of the kind of work I describe above. But it’s one I do love. Here’s the full text.